The Guardians of Heritage: Documenting women’s role in preserving and transmitting intangible cultural heritage in India Back

Heritage consists of inherited objects, traditions and cultures that people have passed down for generations. Cultural heritage may comprise of buildings, artefacts and monuments. As people consider these to be of physical wealth, they are often given increased importance and have the potential to be preserved well. This type of cultural heritage is known as tangible cultural heritage. Yet there is another aspect of cultural heritage – namely, intangible– that is often overlooked due to its lack of physical form. It includes folklore, oral knowledge, customs, beliefs and knowledge, whose preservation is necessary, especially in today’s rapidly modernising and globalising world, where traditional practices are often lost in the quest for progress.

Individuals exercise a degree of liberty in how they choose to interpret intangible cultural heritage through framing. According to Professor Robert M. Entman, ‘To frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described.’1 Applying this definition specifically to intangible heritage, we can see how ICH is framed in the form of performances, stories and practices that helps people, as arbiters of culture, create their perception of reality, and exercise agency over the aspects of family, community, and national heritage and histories that they choose to connect to.

When we document and learn more about intangible cultural heritage and the role that individuals play in framing, creating and sharing it, it becomes evident that it is preserved and transferred, in large part, by a few diverse communities; one of these being women. Research conducted by UNESCO during the International Symposium on the Role of Women in Transmission of Intangible Cultural Heritage concludes that women play a vital role in shaping culture and spreading cultural identity. This is certainly true in India, where in most regions, particularly rural areas, women play a dominant role in bringing up children and taking care of the family, and in the process, share their communal and cultural languages, beliefs and various other forms of cultural heritage with them. This article takes a sweeping survey of several different types of heritage items to examine how exactly the owners assign cultural meaning and value to these items, making them worthy of “heritage” status. Although these items themselves are tangible, they contain histories of various families and communities, enabling them to serve as physical markers or reminders of intangible heritage.

For example, traditional and communal cuisines are passed down from generation to generation, and play a vital role in shaping one’s interpretation of his or her own culture. An interviewee told me about Bharwan Karela. Bharwan Karela is a popular North Indian dish that consists of a karela, also known as bitter gourd, with a stuffing which is made out of a mixture of ground spices. It is meant to be eaten with parathas or rolls. This recipe has been passed down to the younger generation in the family’s house in Kanpur. It was originally introduced by the contributor’s husband’s grandmother, and has been a family favourite ever since. As there were 50 people living in the same house, this dish helped bring the family together at meal times. The contributor also mentioned the following information- ‘This bharwan karela is at least a 100-year-old recipe and it has travelled the world. Anyone, old or young, traveling out of Kanpur, out of India will get this made in quantity and take it with them to be eaten with parathas/ rotis.’2 Thus, we can see that the dish has travelled the world, which helps bring families together and creates communal bonds. It gives a sense of pride in one’s own culture and heritage.

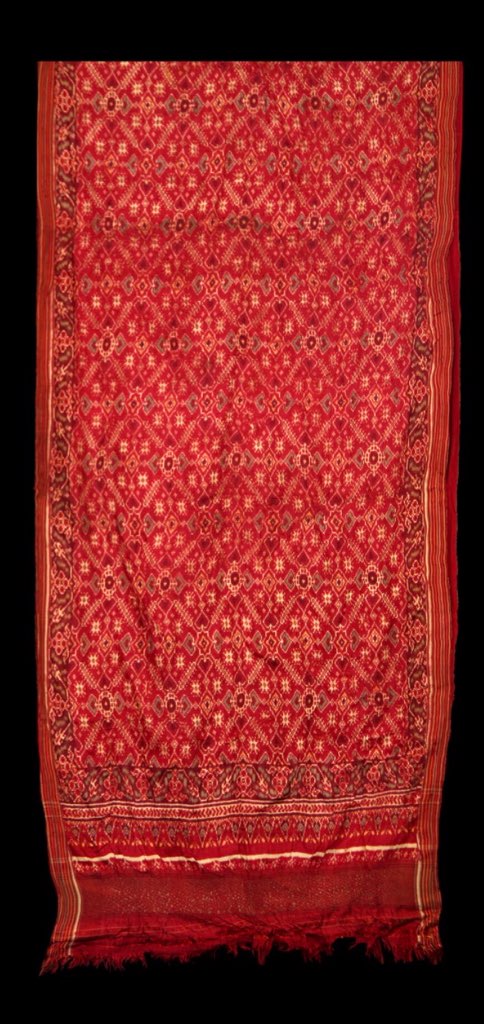

Textiles are also used as symbols of one’s heritage. By drawing from unique embroidery techniques, materials, and skills they come to represent the diverse regions and communities from which they originate. These pieces are often passed down through generations, and the history behind the clothing goes back over hundreds of years.

Patola sarees, for example, originated in Patan, Gujarat. These silk sarees are made through the double ikat dyeing and weaving process. Historically, these sarees were only worn by women from aristocratic and royal families. The process of making these sarees is laborious, sometimes taking up to one year to weave a single piece. Every colour has a unique place in the saree and the design has to be carefully aligned while weaving. A distinctive feature of the Patola loom is that it is tilted to one side and requires two people to sit and work together on just one saree. This Patola has been with the contributor’s family since the 1950s.

Just as food connect to the ancestry of an interviewee’s community, and well as her personal or family history, textiles also showcase the distinctive regional techniques and confer a sense of connection and community to those who wear them.

Other items help create a sense of identity linked to a broader regional or national history. Silverware, for example, is often linked to the old royalty and aristocrats, or to traditional food practices that date back, in some cases, to Vedic times. The tableware chosen by the contributors includes Paan daan, also known as betel case or a container used for storing paan. Paan is a popular preparation eaten in India; it is made out of betal leaf and areca nuts. The photograph of the paan daan seen below is a family heirloom. It has been made by craftsmen who were highly skilled at the ‘Ganga-Jamni’ metalwork. This piece has been done with gold and silver inlays and overlays. It has two compartments, one for storing paan and the other for various other food items. The contributor likes to store food items that have been finely cut and spread in the second tier. She stores foods such as lime, catechu and roasted fennel.3

Then, there is religion, a community in and of itself, in which individuals find a sense of belonging. Religious items serve to facilitate those community bonds, as they enable one’s beliefs and practices to become a reality, as well as form a closer connection to deity being worshipped. An interviewee shared an image of Chandao Sahib. A Chandao Sahib, also known as Chandani is an important element used to worship Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism. It is a canopy that is placed above the Guru Granth Sahib, the religious scripture of Sikhism, which is kept on a raised platform. The Chandao Sahib is made of velvet with intricate Zardozi or Dabka embroidery. The contributor said- ‘I am blessed to be in possession of a rare & antique Chandao, an old work of art, with intricate Zardozi embroidery, done by an old family of artisans settled in the town of Amritsar (Punjab) since the end of the Mughal empire. This was handed down several generations within my family. It is very close to my heart & adorns the highest seat of honour in my home.’4

In contrast, jewellery shared conferred a sense of connection to national history. Chandbalas are earrings that are very popular in India. They are said to have originated in the Mughal or Nizam Era in the city of Hyderabad, India. Chandbalas can also be traced back to the Rajput Dynasty. These earrings consist of two crescent moons, set with a variety of stones, such as diamonds, pearls, enamel, and rubies. The contributor states ‘These chandbalas have been in our family for over hundred years. It belonged to my husband’s great grandmother and has been passed down the generations’.5

Architecture as heritage is also inextricably linked to a country’s history, in that it reflects a country’s interactions with other cultures and nations, whether through trade or colonisation. Architecture shows us how people in various communities once lived, both extravagant and simple. The photograph of this gloriously restored staircase is from a Parsi home, built in 1920 Art Deco style, in the city of Mumbai, India. Art Deco, also known as Deco, is a style of visual arts, architecture and design that originated near France before the First World War and was similarly emergent in Mumbai at a time when businesses were flourishing and patrons wanted international trends in their homes to reflect luxury and modernity. This staircase is made out of teak wood and is located in Bandra, Mumbai. The contributor described the staircase as a ‘work of art’ and a ‘living sculpture’.6

In my interviews, women shared stories ranging from the hustle and bustle of their grandmother’s kitchens, to the quiet moments when their mothers instructed them on how to pray. They spoke about the heyday of their family’s business in 1930s Mumbai, and the hopes and aspirations their aunts and mothers held for them as they crossed the threshold into their new homes as young brides.

The stories, memories, and heritage objects were wide-ranging. What they shared in common, however, was the active role that women play in assigning meaning and value to rituals and items, and passing these on to the other young women in their families. While women’s roles in traditionally feminine areas such as cooking, sewing, decorating and housekeeping are often dismissed as trivial, it is within these domains that women do the important work of shaping culture, community, identity, and fundamentally defining intangible cultural heritage at the family, community, and national levels.

The Article was submitted by: Noor Tarun Sawhney, Vasant Valley School, New Delhi, India

(Noor interned with the ICH Division in the year 2020)

End Notes

- Robert M. Entman, “Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm”, Journal of Communication (Autumn 1993), 51-58.

- Pragati Gupta, Interview by Noor Tarun Sawhney (June `5, 2020).

- Iram Sultan, Interview by Noor Tarun Sawhney (June 28, 2020).

- Pawan Sabharwal, Interview by Noor Tarun Sawhney (June 21, 2020).

- Priya Goel, Interview by Noor Tarun Sawhney (June 16, 2020).

- Shireen Gandhy, Interview by Noor Tarun Sawhney (June 21, 2020).

References

Entman, Robert M. “Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm.” Journal of Communication (Autumn 1993): p. 51-58.

Gandhy, Shireen. Interview by Noor Tarun Sawhney. Personal interview. New Delhi, 21 June, 2020.

Goel, Priya. Interview by Noor Tarun Sawhney. Personal interview. New Delhi, 16 June, 2020.

Gupta, Pragati. Interview by Noor Tarun Sawney. Personal interview. New Delhi, 15 June, 2020.

“INTACH Intangible Cultural Heritage.” Cross Section. Accessed 15 June 2020. intangibleheritage.intach.org.

“Intangible Cultural Heritage”. Wikipedia. Accessed 08 July 2020. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intangible_cultural_heritage.

“International Symposium on the Role of Women in Transmission of Intangible Cultural Heritage”. Intangible Cultural Heritage. Accessed 06 July 2020. ich.unesco.org/doc/src/01851-EN.pdf.

“My Heritage.” ICH Archive. Accessed 10 June 2020. icharchive.intach.org/Myheritage/Index.

Radharaman, K. “Why Textiles are a part of our National Heritage.” Angadi Galleria. Accessed 23 June 2020.

www.angadigalleria.com/textiles-part-national-heritage/.

Sabharwal, Pawan. Interview by Noor Tarun Sawhney. Personal interview. New Delhi, 21 June, 2020.

Shalaginova, Iryna. Understanding Heritage, BTU Cottbus – Senftenberg, 2012.

“Significance of Indian Jewellery.” Bank Bazaar. Accessed 11 July 2020. www.bankbazaar.com/gold-rate/significance-of-indian-jewellery.html.

Sultan, Iram. Interview by Noor Tarun Sawhney. Personal interview. New Delhi, 28 June, 2020.

“Tableware”. Wikipedia. Accessed 14 June 2020.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tableware.

“What is Cultural Heritage?” Khan Academy. Accessed 10 July 2020.www.khanacademy.org/humanities/special-topics-art-history/arches-at-risk-cultural-heritage-education-series/arches-beginners-guide/a/what-is-cultural-heritage.

“What is Intangible Cultural Heritage?” Intangible Cultural Heritage. Accessed 02 July 2020.ich.unesco.org/doc/src/00157-EN.pdf.